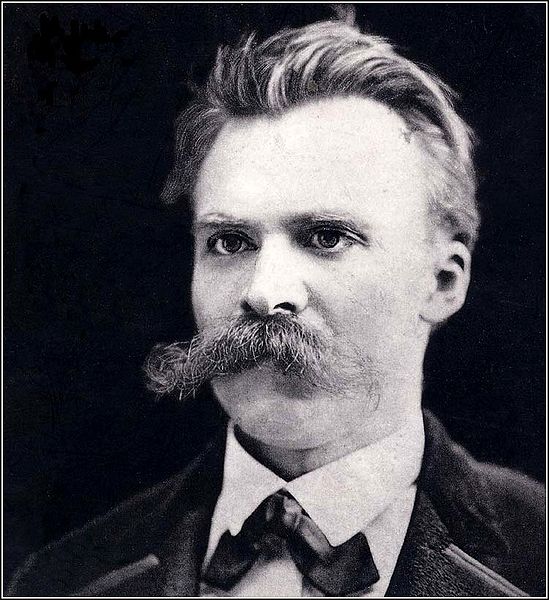

Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy presents a profound critique and revaluation of traditional moral values. His work fundamentally questions the very nature of morality, its origins, and its implications for human flourishing. This discussion explores Nietzsche's critical project against conventional morality, his conception of higher types, and the societal and psychological ramifications of rejecting traditional ethical systems.

Critical Reappraisal of Morality

Nietzsche is well-known for his sweeping critique of morality as it existed in his time, encompassing elements of Christianity, Kantian ethics, and utilitarianism. He proposed that traditional moral values are fundamentally destructive to the potential for human greatness. Nietzsche's declaration of 'the death of God' signifies more than mere atheism; it marks the collapse of the traditional moral framework that had relied on a divine authority for its validity. He asserts that with God no longer at the center, “the values we still continue to live by have lost their meaning, and we are cast adrift”[4]. Nietzsche views contemporary morality as an incoherent pastiche, lacking the robust foundation that had once given it structure.

Nietzsche’s analysis includes the notion of 'ressentiment,' which he describes as a reaction of the oppressed who, in their powerlessness, develop a morality that inverts the values of the powerful. This moral framework prioritizes altruism and compassion, but serves, according to Nietzsche, as a means of spiritual revenge against those who are naturally superior. He observes: “The morality of pity… is perhaps the most general effect and conversion which Christianity has produced in Europe”[3]. Through this lens, Nietzsche critiques the very acts of selflessness and compassion that are often celebrated, arguing that they actually stem from a place of weakness rather than strength.

The Concept of the Higher Type

Central to Nietzsche's moral philosophy is the delineation between 'higher types' and the masses. He posits that the true flourishing of humanity depends on the development and empowerment of exceptional individuals who can transcend the mediocrity of societal morals. Nietzsche’s higher types are characterized by autonomy, creativity, and the ability to affirm life amid suffering. He insists that 'the flourishing individual… will be one who is autonomous, authentic, able to ‘create themselves,’ and to affirm life'[3].

The term 'Übermensch' or 'overman' often encapsulates this ideal. The Übermensch celebrates life in its entirety, embodying the values that promote health, vitality, and artistic expression. Nietzsche's vision of the Übermensch emphasizes that the creation of values must come from individuals who have wrested their existence from conventional morality—those who assert their own will to power to generate new, life-affirming values. 'Higher types' arise from a mixture of strong drives that coalesce into a coherent self, capable of self-overcoming and actualizing their potential[1][4].

The Threat of Nihilism

Nietzsche warns that the prevailing morality of his time, particularly one rooted in pity and self-denial, cultivates a nihilistic outlook that poses a serious threat to human creativity and excellence. This moral framework ultimately leads to despair, as it denies the inherent value of suffering and struggle, instead portraying them as inherently negative. Nietzsche states that “the morality of compassion… is the most uncanny symptom of our European culture”[3].

In this context, Nietzsche identifies a significant dilemma: while traditional moral values may have provided a semblance of meaning and order, their foundation has been irreparably undermined. The result is a cultural shift where values become ephemeral and trivial, leading individuals to live passive lives disconnected from their potential. He identifies this outcome with the “last man,” a figure representative of a society that has given up on striving for greatness in favor of comfort and security[3][4].

Value Creation in a Post-Moral Framework

Nietzsche's radical revaluation of ethics does not leave a moral vacuum; instead, he advocates for a creative approach to values. He believes that individuals can and must create their own values in response to the new realities of a post-religious world. This creative process is not arbitrary; it requires deep self-awareness and an understanding of one’s own drives and instincts. Nietzsche encourages individuals to recognize and assert their unique perspectives, stating that one should treat life as a work of art, shaping it with intention and purpose.

Artistry plays a crucial role in this value creation; Nietzsche argues that 'we possess art lest we perish of the truth'[4]. This suggests that while the quest for absolute truth may lead to nihilism or despair, the pursuit of art and self-expression helps individuals assert their values against an indifferent universe.

Ultimately, Nietzsche asserts that “the man who creates values will feel responsibility for himself in the severest sense: he is bound to life in the world without guarantee and must see it as an artistic endeavor”[4]. The act of creating values, therefore, requires courage and a willingness to embrace life’s uncertainties, presenting a stark contrast to the moral systems that seek to impose rigid constraints on individual expression.

Conclusion

Nietzsche’s impact on morality is profound and multifaceted. By dismantling the foundations of traditional values based on external authority, he opens the door for a new ethical landscape that prioritizes individual creativity and the affirmation of life. Nietzsche’s concerns about nihilism, the development of higher types, and the necessity of values created through individual will challenge contemporary philosophical thought and invite ongoing engagement with his ideas. His work remains a crucial touchstone for discussions about the future of morality in a world increasingly detached from its traditional underpinnings, urging humanity to embrace its capacity for self-creation and life affirmation in the face of existential uncertainty.

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalized discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).