Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalised discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Transcript

- **DIY Paper Flowers**: Kids will enjoy making colorful paper flowers to decorate their rooms, using cupcake liners and floral wire. - **Rock Painting**: A simple and engaging project where kids paint rocks that can be displayed indoors or in the garden. - **Toilet Paper Roll Binoculars**: Create binoculars from toilet paper rolls for outdoor adventures like bird watching. - **Paper Bag Kite**: Kids can use paper lunch bags to craft kites and decorate them for spring flying fun. - **Slime Making**: An entertaining activity where kids learn to make their own colorful, stretchable slime from common household ingredients. - **Tissue Paper Butterflies**: Kids can craft colorful butterflies using coffee filters and markers, perfect for spring. - **Handprint Dish Towels**: Memorialize children's handprints on dishtowels, creating lasting gifts or keepsakes. - **DIY Terrarium**: A fun way for kids to create a mini indoor garden using jars, soil, and small plants. - **Egg Carton Flowers**: Transform egg cartons into beautiful flowers that last longer than the real ones. - **Pasta Crafts**: Dye pasta to make colorful art projects like necklaces or decor that encourages creativity. - **DIY Bath Bombs**: Older kids can create their own bath bombs, adding a fun twist to bath time. - **Rock Creatures**: Use painted rocks to create animal figures, a fun twist on a classic rock painting project. - **Cardboard Tube Binoculars**: Craft binoculars using cardboard tubes to encourage imaginative play during nature walks. - **DIY Bubble Wands**: Create homemade bubble wands from simple materials, perfect for summer play and parties. - **Fairy Houses**: Engage kids in crafting fairy houses from recycled materials to spark imaginative play. - **Finger Puppets**: Simple projects that introduce creative storytelling with easy-to-make finger puppets. - **DIY Sidewalk Chalk**: Teach kids to make their own sidewalk chalk for colorful outdoor artwork. - **Pizza Box Bird Feeder**: Recycle pizza boxes into bird feeders that help kids learn about nature. - **DIY Paint Brushes**: Different everyday materials become brushes for a fun painting experience. - **Clothespin Airplanes**: Kids can craft airplanes with clothespins for imaginative play during outdoor activities. - **DIY Rainbow Wand**: Create a colorful wand using ribbons and sticks, perfect for dress-up and imaginative play. - **Paper Plate Masks**: Use paper plates to make fun masks for imaginative games and roles. - **Bubble Refill Station**: Set up a DIY bubble refill station to keep outdoor play going longer with minimal mess. - **Painted Rocks**: Kids can express themselves by painting rocks with different designs for decoration. - **Mini Garden Markers**: Craft personalized markers with wooden sticks for kids to label their garden plants. - **Bottle Cap Magnets**: Turn bottle caps into fun decorative magnets, great for crafting and skills development. - **Clothespin Dolls**: Craft dolls using clothespins and fabric, letting kids exercise their designing skills. - **Cupcake Liner Flowers**: Create bright flowers from cupcake liners, a quick and simple craft. - **Nature Mandalas**: Use natural materials like leaves and flowers to create beautiful, transitory art. - **Outdoor Painting**: Set up a painting station outdoors, allowing kids to express creativity in nature. - **Recycled Robots**: Collect various recyclable materials to build unique robots, fostering creativity and engineering skills. - **Marble Runs**: Create a DIY marble run using cardboard tubes and cups, combining creativity and physics. - **DIY Suncatchers**: Make colorful suncatchers from transparent materials that catch sunlight beautifully. - **Pine Cone Bird Feeders**: Kids can make bird feeders using pine cones and peanut butter, encouraging wildlife observation. - **Yogurt Cup Monsters**: Transform yogurt cups into silly monsters for playtime, using craft supplies like paper and markers. - **Spring Flowers in Jars**: Create spring flowers using tissue paper and mason jars, suitable for decorating any space. - **Felt Flower Bouquet**: Kids love making no-sew felt flowers for decorating their rooms or giving as gifts. - **Upcycled T-Shirt Bracelets**: Turn old t-shirts into stylish bracelets while discussing sustainability and creativity.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Global health organizations are collectively enhancing their responses to the threats posed by emerging infectious diseases through strategic initiatives that prioritize research and development (R&D), the formulation of guidelines, and improved surveillance measures. These efforts aim not only to combat current health threats but also to prepare for potential future outbreaks.

Identification and Prioritization of Pathogens

The World Health Organization (WHO) has taken significant steps in identifying and prioritizing pathogens that pose substantial risks for global health. In a recent update, WHO has convened over 300 scientists to discuss and evaluate over 25 virus families and bacteria, including 'Disease X,' which reflects an unknown pathogen that could cause severe outbreaks. This effort culminates in a prioritized list of pathogens that require further research and investment in vaccines, diagnostics, and treatment[2].

Dr. Michael Ryan, Executive Director of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, emphasized the importance of targeting these priority pathogens, stating, “Targeting priority pathogens and virus families for research and development of countermeasures is essential for a fast and effective epidemic and pandemic response.' This systematic approach allows for the identification of critical gaps in preparedness and response capabilities, ensuring that funds and resources are allocated where they are most needed[2].

Advancements in Research and Development

WHO’s R&D Blueprint for epidemics outlines specific research roadmaps for these priority pathogens. These roadmaps address knowledge gaps and research priorities necessary for developing effective countermeasures. The Blueprint also facilitates clinical trials for vaccines and treatments against these high-priority pathogens, enhancing the readiness of health systems to respond to potential outbreaks[2].

In addition, a review examined the availability and utility of preclinical animal models for high-priority infectious diseases. This research highlights the need for effective prophylactic and therapeutic approaches to infectious diseases and suggests that better animal models could significantly enhance the understanding and control of these diseases[3]. The focus on improving the landscape for vaccine development, antibodies, and small molecule drugs reflects a proactive stance against infectious diseases[3].

Surveillance and Detection Strategies

To mitigate the impact of emerging infectious diseases, organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) play a crucial role in conducting extensive surveillance and epidemiological studies. For example, the CDC has been actively engaged in tracking infectious diseases such as Streptococcus dysgalactiae and Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM), identifying significant health risks and mortality rates associated with these infections. The findings from CDC studies reveal substantial increases in incidence rates of certain infections and the associated mortality risks, which inform public health strategies[1].

Innovative methodologies for enhancing surveillance have also been reported. For instance, a systematic review indicated that the consistent monitoring of diseases such as mpox and extrapulmonary NTM through comprehensive epidemiological studies is vital. This brings to light the critical nature of ongoing research in understanding the transmission dynamics, risk factors, and effective management strategies for these diseases[1].

Addressing Socioeconomic Factors and Health Disparities

Global health organizations are increasingly aware of the social determinants of health that contribute to the spread and impact of infectious diseases. Studies have indicated that regions with limited healthcare infrastructure see higher incidences of diseases such as histoplasmosis, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions in these vulnerable populations. Increasing awareness and improving access to healthcare services are essential strategies in addressing these disparities[1].

Furthermore, WHO emphasizes the socioeconomic impact of infectious diseases in developing its priorities. By considering not only the biological aspects of pathogens but also their broader social implications, organizations can better establish equitable health interventions. This multifaceted approach is necessary to ensure that all populations benefit from advances in healthcare and that emerging health threats are managed in a way that considers varying global contexts[2].

Conclusion

The collaborative efforts of global health organizations, particularly the WHO and CDC, are critical in confronting emerging infectious diseases. By prioritizing pathogens for research, enhancing preparedness through better surveillance and diagnostics, and addressing the social determinants of health, these organizations are working to build resilient healthcare systems. Through continuous investment in research and a robust framework for international cooperation, global health organizations aim to safeguard public health against current and future infectious disease threats. The collective emphasis on preparedness, response, and equitable health intervention underscores a growing recognition of the complex nature of global health challenges in today's interconnected world.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

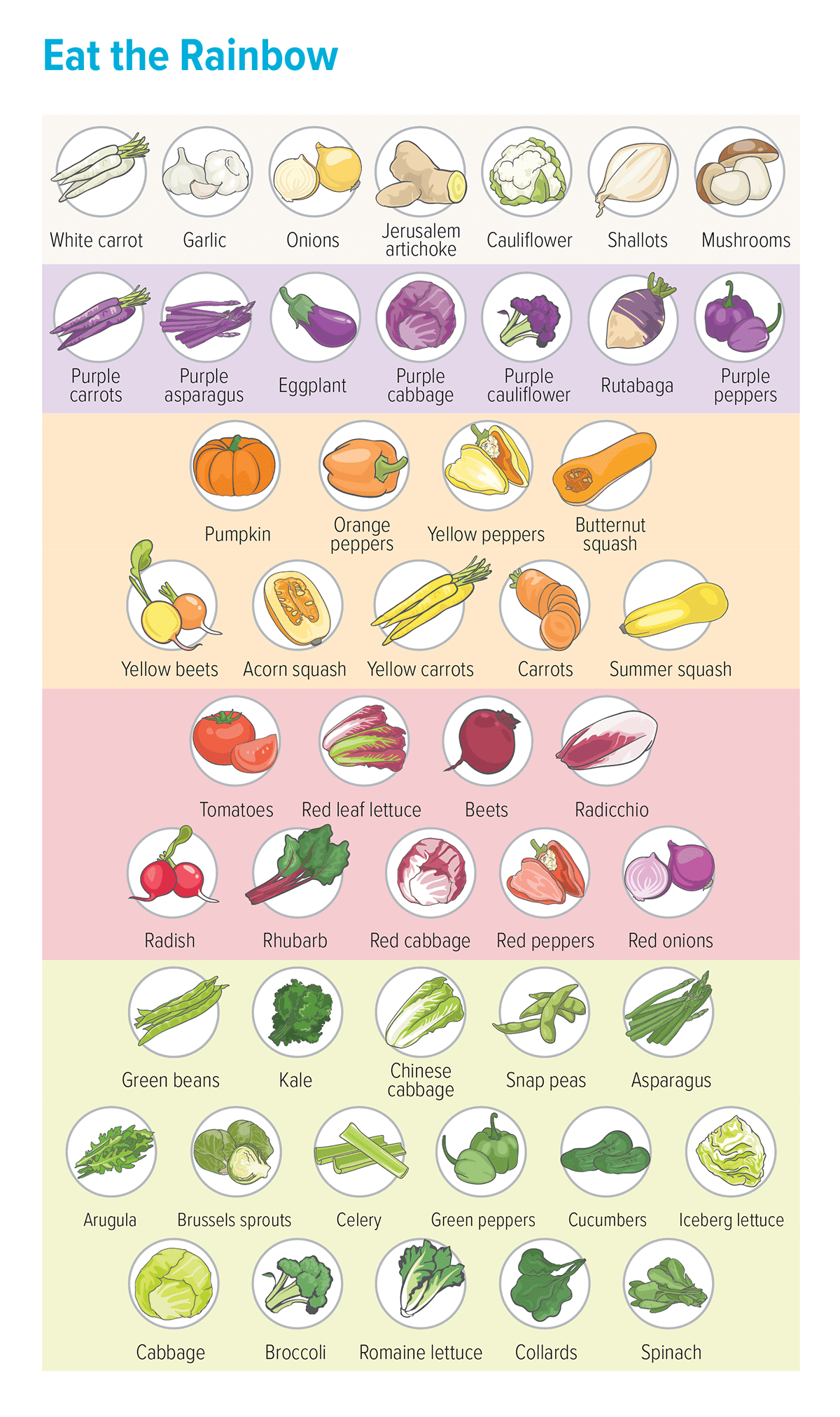

Nutrition plays a critical role in supporting athletic performance, recovery, and overall health. Proper nutrition is not merely about eating well; it involves strategic dietary choices that meet the energy and nutrient demands of an athlete's body. This report synthesizes insights from various sources to elucidate how nutrition influences athletic performance and recovery.

Energy Requirements and Macronutrient Composition

Athletes have unique energy needs due to their higher levels of physical activity compared to non-athletes. A well-balanced intake of macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—is essential for optimal performance. Adequate energy intake not only fuels training and competition but also helps prevent conditions such as Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), which can lead to decreased performance and negative health outcomes[3][5].

Carbohydrates serve as a primary energy source, particularly for high-intensity exercise. Research indicates that athletes should consume around 5 to 7 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight daily to maintain energy levels during intense training and competitions[3]. Additionally, eating carbohydrates before exercise is crucial for sustaining intensity and focus, while post-exercise carbohydrate consumption aids in recovery and replenishes glycogen stores[1][5].

Protein for Muscle Repair and Growth

Protein is vital for muscle repair and growth, especially after exertion. Current recommendations suggest athletes should aim for an intake of 1.2 to 2.3 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day[5]. Importantly, there is a ceiling to how much protein the body effectively utilizes per meal, estimated to be about 25 to 30 grams[5]. Timing of protein intake also matters; focusing on protein for recovery after exercise helps maximize muscle protein synthesis (MPS)[1][4].

Research supports that consuming 20 grams of high-quality protein shortly after exercise can significantly enhance muscle recovery and growth. Additionally, protein intake distributed evenly across meals throughout the day is encouraged to optimize MPS[5]. For athletes recovering from injuries, a higher protein intake is necessary to combat muscle loss and promote healing[4].

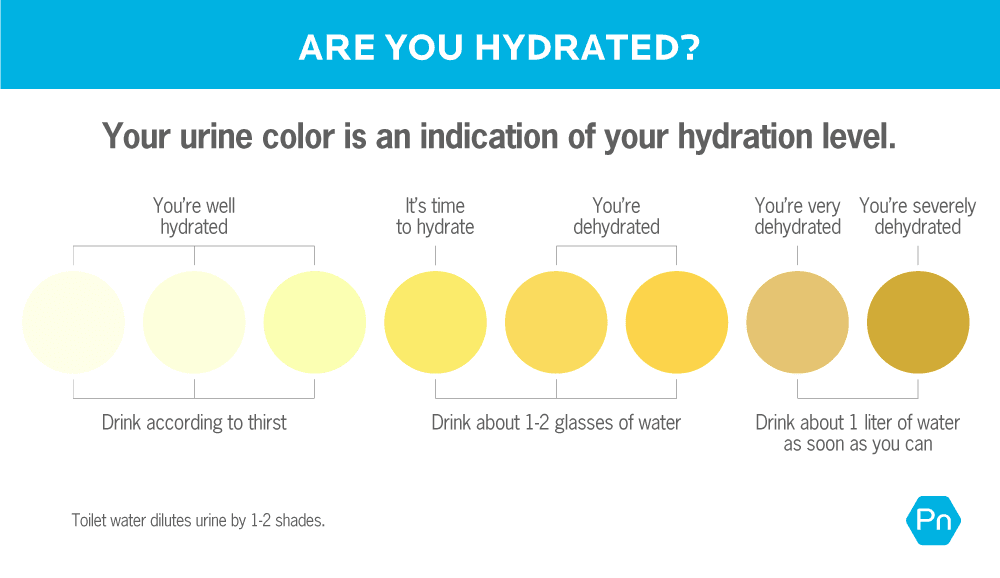

Hydration and Its Implications

Staying hydrated is fundamental for maintaining performance levels and promoting recovery[5]. Fluid losses during exercise can lead to decreased performance; therefore, athletes should aim to drink 3 to 4 liters of fluids daily, adjusting for individual sweat rates and climatic conditions[3][5]. Hydration strategies should also include replacing electrolytes lost during intense or prolonged exercise to prevent issues such as hyponatremia, particularly in hot conditions[1][3].

Micronutrients and Supplementation

Micronutrients, including vitamins and minerals, are crucial for various metabolic processes that impact athletic performance. Athletes often experience deficiencies in vitamins D, magnesium, and calcium, which can affect their energy levels and recovery[3][5]. Supplementation can help address these gaps, but it’s important to focus on achieving these nutrients through a varied and nutrient-rich diet whenever possible[1].

In addition to traditional macronutrients and micronutrients, the emerging interest in supplementation involving probiotics, prebiotics, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) highlights the potential for gut health to influence athletic performance[2]. Research suggests that a balanced gut microbiome may enhance energy metabolism and exercise capacity, although more targeted studies are needed in this area[2].

Nutrition Strategies for Performance Enhancements

Several dietary strategies can optimize athletic performance. Implementing carbohydrate loading can be beneficial for endurance events lasting longer than 90 minutes, while proper nutrient timing—such as consuming specific macronutrients at pre-determined intervals—can aid muscle recovery and improve performance[1][4]. This concept of nutrient timing involves prioritizing carbohydrate intake before and after workouts and balancing protein intake to enhance recovery[3][4].

Adopting a well-structured dietary plan not only supports immediate performance needs but also fosters long-term athlete health. Ensuring that meals are rich in high-quality proteins, complex carbohydrates, and healthy fats is essential for maintaining energy levels and maximizing recovery post-exercise[5].

Conclusion

In summary, optimal nutrition is fundamental to athletic performance. It aids in energy provision, muscle recovery, and effective hydration, while also addressing micronutrient needs and encouraging the use of dietary supplements where appropriate. A careful approach to nutrition, grounded in scientific principles, equips athletes with the tools they need to excel in their sport and promotes sustainable health practices that can benefit them in the long run. Integrating these principles into daily routines ensures that athletes can sustain high performance and recover effectively from intense training efforts and competition.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

The key differences between GPT-5 Mini and full GPT-5 in terms of vision capabilities are as follows:

Performance: It's noted that 'mini performs the same as main,' suggesting that GPT-5 Mini matches GPT-5 in performance across various tasks, including vision capabilities like object detection and image captioning[4].

Architectural Features: GPT-5 is described as a 'proprietary, multimodal system supporting text and vision inputs,' and it features a larger context window of 400,000 tokens, which is beneficial for handling long documents and complex workflows. This specific detail about the extended context window does not apply to GPT-5 Mini[3].

Comparative Testing: Users can run side-by-side tests for both models on tasks like OCR and other vision-related tasks in platforms like the Roboflow Playground, which allows for a direct performance comparison[1][5].

In summary, while GPT-5 Mini may match the main model's performance in specific tasks, GPT-5 possesses additional advanced features beneficial for more complex applications.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalised discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Generative AI is shaping the music industry by enabling innovative content creation and raising concerns about intellectual property (IP) rights. The industry has achieved a consensus on limiting AI deepfakes and controlling AI deployment, with major players collaborating to manage these challenges. Despite initial fears, the flood of AI-generated content has not significantly impacted label revenues. Instead, Generative AI is seen as a tool for professional artists to enhance their music production and marketing strategies, reflecting a balanced approach towards its adoption in the music space[1].

As the industry explores applications for Generative AI, it faces ongoing legal challenges related to copyright. Significant concerns remain about the potential use of copyrighted material without proper licensing, leading to the introduction of proposed regulations aimed at protecting artists' rights[1].

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Introduction to Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a powerful class of neural networks designed to handle sequential data, achieving state-of-the-art performance in tasks such as language modeling, speech recognition, and machine translation. However, RNNs face challenges with overfitting, particularly during training on limited datasets. This led researchers Wojciech Zaremba, Ilya Sutskever, and Oriol Vinyals to explore effective regularization strategies tailored for RNNs, specifically those using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units.

The Problem of Overfitting in RNNs

Overfitting occurs when a model learns not only the underlying patterns in the training data but also the noise, leading to poor generalization on new, unseen data. Traditional regularization methods like dropout have proven effective for feedforward networks but are less effective for RNNs due to their unique architecture. The paper highlights that standard dropout techniques do not appropriately address the recurrent nature of LSTMs[1].

Introducing Dropout for LSTM Regularization

The authors propose a new way to implement dropout specifically for LSTMs. The key idea is to apply dropout only to the non-recurrent connections in the LSTM units, while keeping the recurrent connections intact. This approach helps preserve the long-term dependencies crucial for RNN performance. The dropout operator function, denoted as D, is implemented to randomly set a subset of its inputs to zero, effectively allowing the model to generalize better during training[1].

In mathematical terms, the proposed model maintains the essential structure of LSTMs while introducing the modified dropout strategy, which prevents the model from discarding vital information over multiple time steps[1].

Experimental Setup

The research incorporates extensive experimentation across different domains such as language modeling and image caption generation. For language modeling, the authors utilized the Penn Tree Bank (PTB) dataset, which consists of roughly 929k training words. They experimented with various LSTM configurations, ranging from non-regularized to several levels of regularized LSTMs. Results showed significant improvements in performance metrics, particularly in the validation and test sets, when applying their proposed dropout method[1].

In speech recognition tasks, the paper documented the effectiveness of regularized LSTMs in reducing the Word Error Rate (WER), thereby demonstrating the advantages of their approach in practical applications[1].

Results and Findings

The paper's results are telling. For instance, they found that regularized LSTMs outperformed non-regularized models on key performance indicators like validation and test perplexity scores. Specifically, the medium regularized LSTM achieved a validation set perplexity of 86.2 and a test set score of 82.7, highlighting the capacity of the proposed dropout method to enhance model robustness[1].

Further, in tasks involving image caption generation and machine translation, the regularized models exhibited improved translation quality and caption accuracy. This suggests that applying dropout effectively can lead to better long-term memory retention, crucial for tasks requiring context and understanding over extended sequences[1].

Conclusion

The exploration of dropout as a regularization technique specifically tailored for LSTMs underscores its potential to improve performance across various tasks involving sequential data. The findings validate that applying dropout only to non-recurrent connections preserves essential memory states while reducing overfitting. As a result, RNNs can achieve better generalization on unseen datasets, ultimately leading to enhanced capabilities in language modeling, speech recognition, and machine translation. This research not only addresses a critical gap in the application of regularization techniques but also offers practical implementation insights for future advancements in deep learning frameworks involving RNNs[1].

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

Introduction to Transformers in Vision

The study of image recognition has evolved significantly with the introduction of the Transformer architecture, primarily recognized for its success in natural language processing (NLP). In their paper 'An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale,' the authors, including Alexey Dosovitskiy and others, establish that this architecture can also be highly effective for visual tasks. They note that attention mechanisms, fundamental to Transformers, can be applied to image data, where images are treated as sequences of patches. This innovative approach moves away from traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) by reinterpreting images. The paper states, 'We split an image into fixed-size patches, linearly embed each of them, add position embeddings, and feed the resulting sequence of vectors to a standard Transformer encoder'[1].

The Vision Transformer (ViT) Model

The Vision Transformer (ViT) proposed by the authors demonstrates a new paradigm in image classification tasks. It utilizes a straightforward architecture inspired by Transformers used in NLP. The foundational premise is that an image can be segmented into a sequence of smaller fixed-size patches, with each patch treated as a token similar to words in sentences. These patches are then embedded and processed through a traditional Transformer encoder to perform classification tasks. The authors assert that 'the illustration of the Transformer encoder was inspired by Vaswani et al. (2017)'[1].

Training Procedures and Datasets

The effectiveness of ViT emerges significantly when pre-trained on large datasets. The authors conducted experiments across various datasets, including ImageNet and JFT-300M, revealing that Transformers excel when given substantial pre-training. They found that visual models show considerable improvements in accuracy when trained on larger datasets, indicating that model scalability is crucial. For instance, they report that 'when pre-trained on sufficient scale and transferred to tasks with fewer data points, ViT approaches or beats state of the art in multiple image recognition benchmarks'[1].

Results and Comparisons

When comparing the Vision Transformer to conventional architectures like ResNets, the authors highlight that ViT demonstrates superior performance in many cases. Specifically, the ViT models exhibit significant advantages in terms of representation learning and fine-tuning on downstream tasks. For example, the results showed top-1 accuracy improvements over conventional methods, establishing ViT as a leading architecture in image recognition. The paper notes, 'Vision Transformer models pre-trained on JFT achieve superlative performance across numerous benchmarks'[1].

Detailed Performance Metrics

In their experiments, the authors explore configurations of ViT to assess various model sizes and architectures. The results are impressive; they report accuracies like 89.55% on ImageNet and further improvements on JFT-300M dataset variations. Variants such as ViT-L/16 and ViT-B/32 also displayed robust performance across tasks. The authors emphasize that these results underscore the potential of Transformers in visual contexts, asserting that 'this strategy works surprisingly well when coupled with pre-training on large datasets, whilst being relatively cheap to pre-train'[1].

Technical Insights and Methodology

The paper also elaborates on the technical aspects of the Vision Transformer, such as the self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to learn various contextual relationships within the input data. Self-attention, a crucial component of the Transformer architecture, enables the ViT to integrate information across different areas of an image effectively. The research highlights that while CNNs rely heavily on local structures, ViT benefits from its ability to attend globally across different regions of the image.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the strong performance demonstrated by ViT, the authors acknowledge certain challenges and limitations in their approach. They indicate that although Transformers excel in tasks requiring substantial training data, there remains a gap when it comes to smaller datasets where traditional CNNs may perform better. The complexity and computational demands of training large Transformer models on limited data can lead to underperformance. The authors suggest avenues for further research, emphasizing the importance of exploring self-supervised pre-training methods and addressing the discrepancies in model effectiveness on smaller datasets compared to larger ones[1].

Conclusion

The findings presented in 'An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale' illustrate the potential of Transformers to revolutionize image recognition tasks, challenging the traditional dominance of CNNs. With the successful application of the Transformer framework to visual data, researchers have opened new pathways for future advancements in computer vision. The exploration of self-attention mechanisms and the significance of large-scale pre-training suggest an exciting frontier for enhancing machine learning models in image recognition. As the research advances, it is clear that the confluence of NLP strategies with visual processing will continue to yield fruitful innovations in AI.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(814x708:816x710):format(webp)/Iran-Retaliation-022826-02-18dc9641a3344b958b119395bfce995e.jpg)