The Impending Quantum Threat to Cryptography

The advancement of quantum computing poses a significant threat to modern cybersecurity. Widely used public-key cryptographic algorithms like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), which form the backbone of today's digital security, are vulnerable to attacks from future quantum computers. These systems rely on mathematical problems, such as integer factorization, that are computationally difficult for classical computers but could be solved efficiently by a sufficiently powerful quantum computer running Shor's algorithm. This vulnerability creates an urgent need to transition to quantum-resistant solutions to protect sensitive data from the "Harvest Now, Decrypt Later" (HNDL) threat, where adversaries steal encrypted data today to decrypt it once quantum computers are available. Two primary strategies have emerged to address this challenge: Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) and Quantum Key Distribution (QKD). While both aim to provide quantum-safe security, they differ fundamentally in their approach: PQC is a software-based solution rooted in mathematics, while QKD is a hardware-based method grounded in the laws of physics.

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC): The Practical Software Solution

Post-Quantum Cryptography refers to a new generation of cryptographic algorithms designed to be secure against attacks from both classical and quantum computers. Crucially, PQC algorithms are not quantum themselves; they are classical algorithms that run on existing hardware and can be deployed through software updates. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has led a standardization process, selecting algorithms based on mathematical problems believed to be difficult for quantum computers to solve. Key PQC families include lattice-based cryptography, which forms the basis of NIST's primary standards like ML-KEM (Kyber) for key exchange and ML-DSA (Dilithium) for digital signatures, and hash-based cryptography, such as SLH-DSA (SPHINCS+).

Advantages:

* Cost and Deployment: PQC is cost-effective and easy to deploy as it operates on classical computers without specialized hardware, often deliverable via software updates. This makes it a scalable, universal solution.

* Versatility: Unlike QKD, PQC is a general-purpose solution that can be used for both secure key exchange and digital signatures for user authentication. It can operate over various network types, including wireless connections.

* Performance: Standardized PQC algorithms like Kyber and Dilithium have demonstrated competitive, and in some cases superior, performance compared to classical schemes like RSA and ECDH at equivalent security levels.

Challenges:

* Security Foundation: PQC's security relies on the assumed computational difficulty of mathematical problems. While rigorously tested, there is no theoretical guarantee that these algorithms won't be broken by future algorithmic breakthroughs. As one expert notes, "People can’t predict theoretically that these PQC algorithms won’t be broken one day".

* Key and Ciphertext Size: Many PQC algorithms require larger key and signature sizes compared to their classical counterparts, which can increase latency, bandwidth consumption, and storage requirements. This may necessitate infrastructure upgrades to maintain performance.

* Maturity and Implementation Risk: As new algorithms, PQC schemes have not undergone decades of real-world testing like RSA and ECC, posing risks of undiscovered weaknesses or implementation flaws, such as side-channel vulnerabilities.

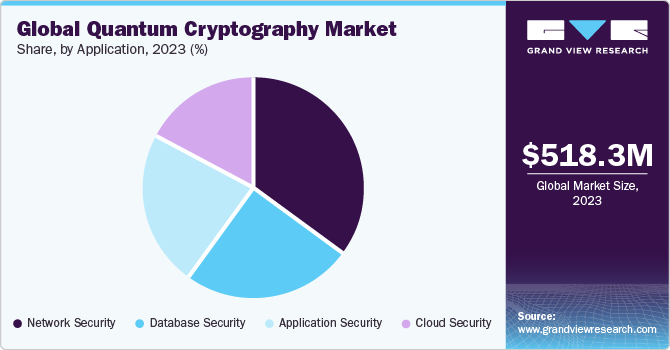

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD): Security Through Physics

Quantum Key Distribution is a hardware-based method for securely exchanging cryptographic keys by leveraging the principles of quantum mechanics. It typically uses photons transmitted over a dedicated optical fiber to establish a shared secret key between two parties. The security of QKD is not based on mathematical complexity but on the fundamental laws of physics.

Advantages:

* Theoretical Security: QKD's primary advantage is its "built-in eavesdropping detection". According to quantum mechanics, the act of measuring a quantum state inevitably disturbs it. This means any attempt by an eavesdropper to intercept the key is immediately detectable, alerting the legitimate users and invalidating the key. This provides a provable, future-proof security that is resistant to advances in computing power.

Challenges:

* Cost and Infrastructure: QKD requires specialized and expensive hardware, including single-photon sources and detectors, as well as dedicated fiber optic connections. This leads to significant deployment costs and major infrastructure changes.

* Range and Scalability: QKD is severely limited by distance due to signal loss in optical fibers; for example, only 0.01% of photons typically travel more than 200 kilometers. Extending this range requires either trusted nodes, which introduce new security vulnerabilities, or quantum repeaters, a technology still under development.

* Lack of Authentication: QKD protocols do not inherently authenticate the source of the transmission, making them vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks. They must be supplemented with classical authentication methods, which often rely on PQC or pre-shared keys.

* Practical Vulnerabilities: While theoretically unbreakable, practical QKD implementations can introduce vulnerabilities. Attacks such as photon number-splitting, where an eavesdropper intercepts extra photons from a weak laser pulse, and side-channel attacks on hardware have been demonstrated against real-world systems.

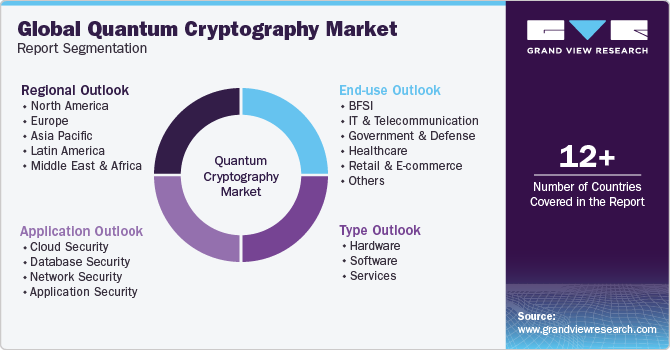

Deployment Decisions: PQC as the Standard, QKD for Niche Applications

When choosing between PQC and QKD, organizations must assess their specific threat models, costs, and scalability needs. For most enterprises, PQC stands out as the more practical and reliable option for achieving quantum security. It is an all-around solution designed to replace quantum-vulnerable cryptography in existing systems with minimal disruption. Major security agencies, including the NSA (USA), NCSC (UK), ANSSI (France), and BSI (Germany), do not recommend QKD as a sole solution and instead prioritize the migration to PQC. The NSA considers PQC to be "more cost-effective and easily maintained" and does not support using QKD to protect national security systems.

QKD's high cost, infrastructure demands, and distance limitations restrict its use to "niche use cases". It is best suited for securing high-value, point-to-point connections where the expense is justifiable, such as linking two data centers or protecting critical government and defense communications. However, it is not considered practical for widespread consumer applications like securing mobile credit card payments. Some experts envision a future where a hybrid approach combines both technologies. As one analyst suggests, "A hybrid of QKD and PQC is the most likely solution for a quantum safe network," where QKD provides theoretical information security and PQC enables scalability. For the immediate future, however, the consensus is clear: PQC is the safer bet for broad deployment.

Conclusion: The Urgent Path to a Quantum-Resistant Future

The transition to quantum-resistant cryptography is one of the most significant cybersecurity challenges of the next decade. While QKD remains a promising field of research that may overcome its limitations with technological progress, PQC is the more mature, flexible, and practical solution available today. With NIST having finalized its first PQC standards, organizations have a clear path forward. The immediate priority for all enterprises is to begin the migration to PQC to safeguard sensitive data against the HNDL threat. This journey involves creating a cryptographic inventory, prototyping PQC implementations to assess performance impacts, and building crypto-agility to adapt to future changes. For now, PQC provides the most viable and comprehensive defense, ensuring that digital infrastructure can remain secure in the quantum era.

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalized discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).