The Widening Adaptation Finance Gap

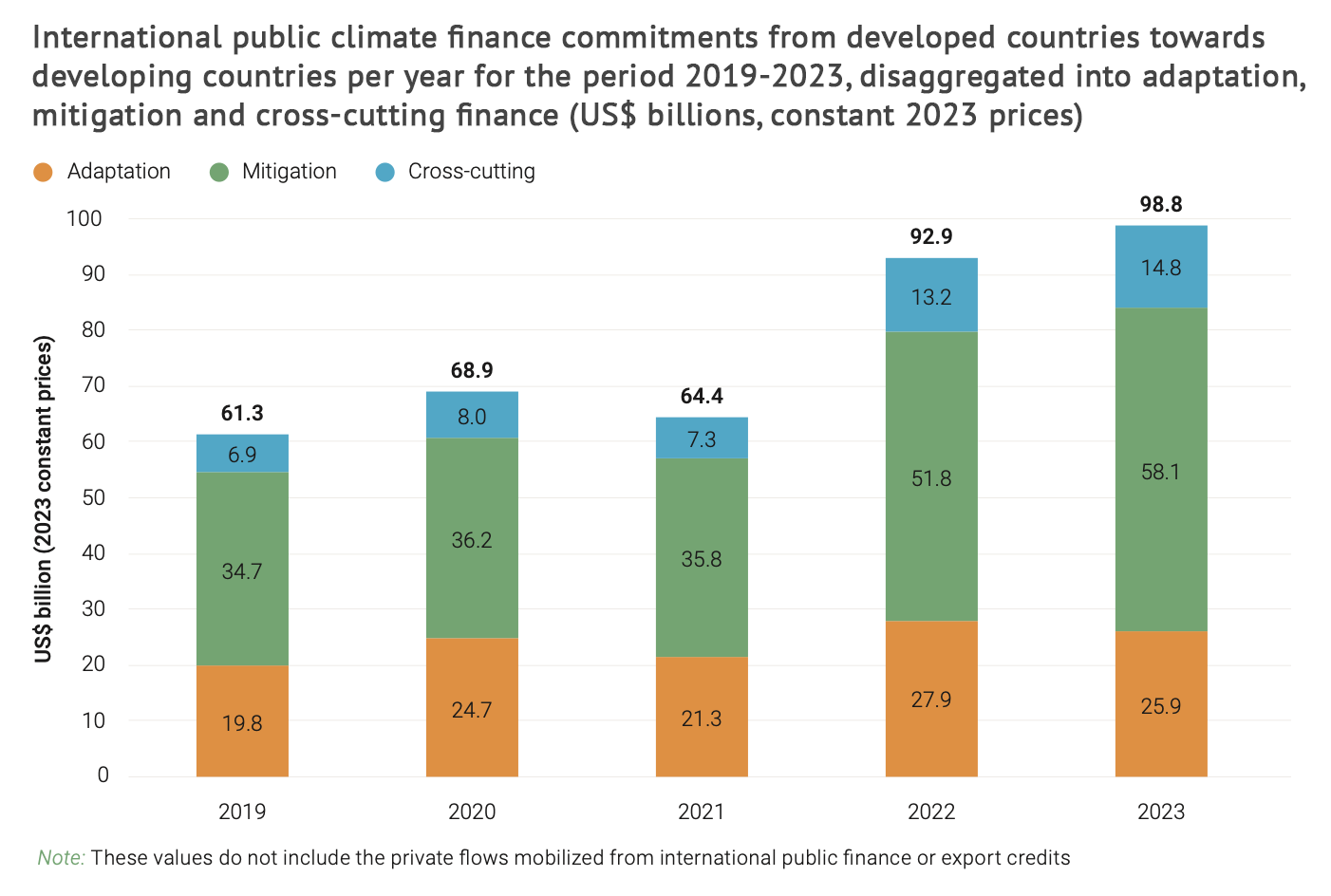

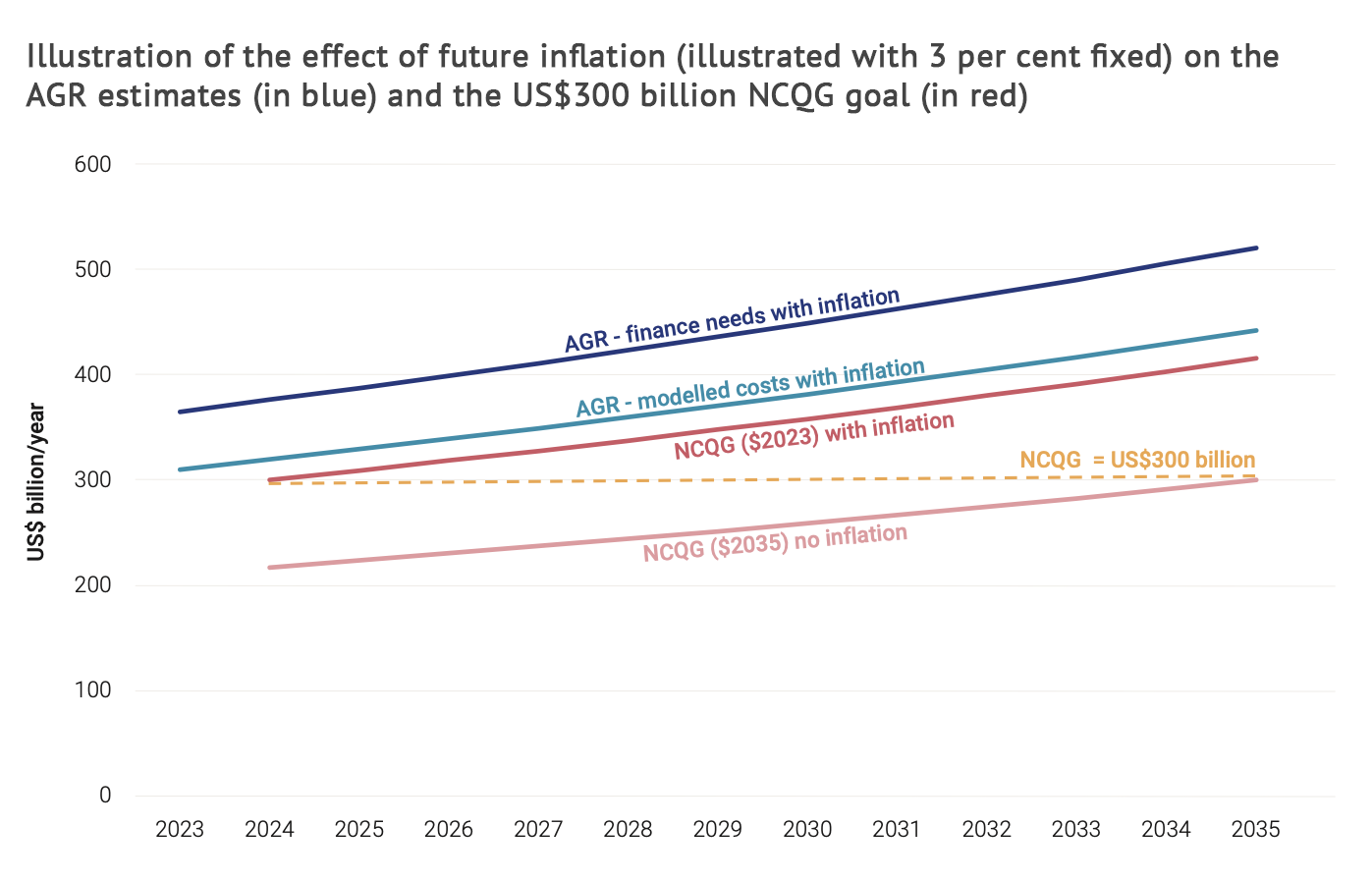

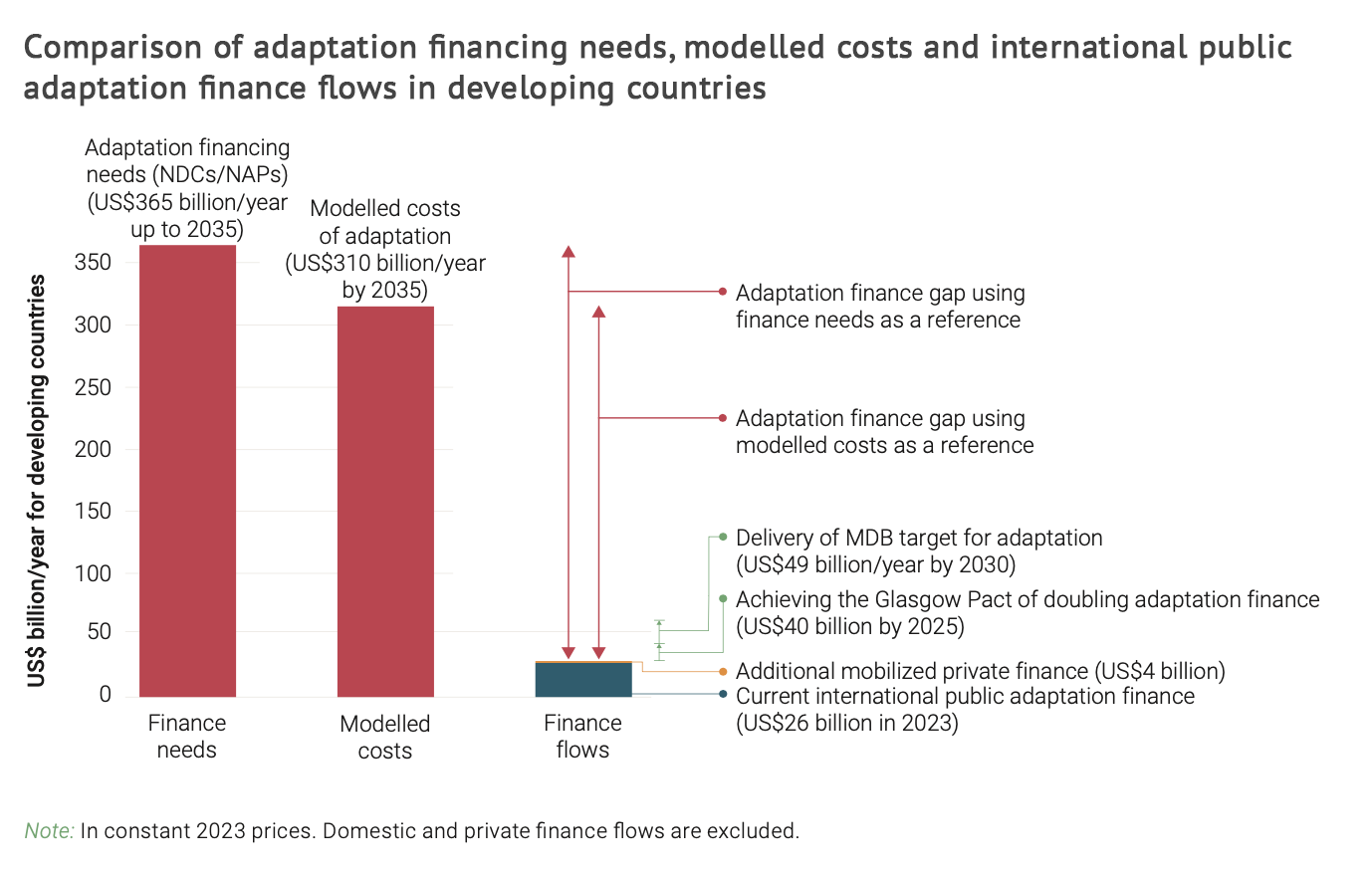

Despite its critical importance, climate adaptation is often viewed as the 'lesser cousin' of mitigation in terms of both focus and finance[1]. This disparity has created a significant funding gap that widens annually[1]. Developing nations are projected to need between $215 billion and $387 billion per year by 2030 for adaptation, yet financing reached only $63 billion in 2021-2022[1]. The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) calculates the current adaptation finance gap for these nations to be in the range of $284-339 billion per year by 2035, meaning their needs are 12 to 14 times greater than current financial flows[3]. Consequently, developed nations are on track to miss their COP26 goal of doubling 2019 adaptation finance levels by 2025[3]. Traditional instruments like debt, equity, and grants are insufficient to meet this demand, as there is not enough traditional capital available, and many developing countries lack the fiscal space to scale this type of finance[1]. Regional needs vary widely; Africa's adaptation costs are projected to reach up to $50 billion annually by 2050, while Small Island Developing States (SIDS) require an estimated 3.4% of their GDP each year for climate adaptation[4].

The Role of Multilateral Development Banks

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are major providers of the climate finance that vulnerable nations need[2]. In 2024, MDBs achieved a record $137 billion in global climate financing, a 10% increase from the previous year, with over $85 billion directed to low- and middle-income economies[10]. However, progress is mixed. While every MDB hit a record high for total climate finance in 2023, funding for adaptation continues to lag behind mitigation[2]. In fact, public money for adaptation from richer nations fell in 2023, partly due to a decline in funding from MDBs[3]. The quality of finance is also a concern, as 67% of MDB climate finance to developing economies between 2019 and 2023 came as investment loans, while the share of grants decreased[2]. This is problematic for the three-fifths of low-income countries already at risk of or in debt distress[2]. In response to calls for reform, MDBs have pledged to provide $120 billion annually in climate finance for low- and middle-income countries by 2030, with $42 billion earmarked for adaptation[10].

Innovative Financial Instruments to Mobilize Capital

To bridge the funding gap, innovative financial instruments are emerging to mobilize significant new capital from the private sector, institutional investors, and philanthropists[1]. These instruments often use creative design and risk-sharing to make investments more attractive[1]. Key approaches include:

- Blended Finance: This method uses catalytic public or philanthropic capital to increase private sector investment[8]. It leverages concessional capital to reduce risk or enhance returns for commercial investors[1].

- Risk-Sharing and Insurance: Instruments like parametric insurance and catastrophe bonds provide quick liquidity after climate disasters[1]. Credit guarantees, where an entity like an MDB covers potential loan defaults, also help de-risk investments for the private sector[1].

- Resilience Bonds and Debt Instruments: The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) launched a climate adaptation bond that raised AUD500 million for climate-resilient infrastructure[1]. Other tools include climate-resilient debt clauses, which allow for a temporary pause on loan repayments after a disaster, and debt-for-nature swaps, where countries receive debt waivers for meeting conservation targets[1].

- Results-Based Finance: These instruments channel funds toward projects that deliver tangible outcomes[1]. Examples include Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) arrangements and adaptation benefits mechanisms, which provide fiscal credits for achieving adaptation goals[1][8].

Community-Level Projects and Nature-Based Solutions

Effective adaptation finance translates into tangible, community-level projects, with a growing emphasis on Nature-Based Solutions (NbS)[4]. NbS offer cost-effective, long-term strategies that enhance resilience while providing co-benefits for biodiversity and local livelihoods[4]. For example, the Landscape Resilience Fund, supported by partners like the WWF and Chanel, invested in Koa, a Swiss-Ghanaian cocoa company[1]. This initial investment helped secure over $5 million in additional private funding to enhance cocoa production and improve farmers’ resilience in Ghana[1]. In Kenya, a blended finance project combined community equity, World Bank grants, and microfinance loans to connect 1,500 households in arid regions to new and improved water infrastructure[8]. In Nepal, a concessional loan from the International Finance Corporation was blended with private equity to help small and medium-sized agribusinesses adopt climate-resilient practices for key crops like rice and maize[8]. Another innovative model is the Quiroz-Chira Water Fund in Peru, which uses a Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) mechanism. Downstream water users, including municipalities and water boards, voluntarily contribute to a fund that finances upstream conservation and ecosystem recovery, protecting the water source for over 500 families and impacting over 18,000 hectares of land[8].

Measuring Resilience to Track Progress and Impact

A critical challenge in climate adaptation is the lack of tools to easily answer the question, 'how resilient are we?'[14]. While many indicators exist to measure social vulnerability and climate hazards, they do not reveal whether the systems that form the core of resilience are functioning effectively[14]. Measuring the progress and outcomes of adaptation strategies is crucial for assessing and optimizing their effectiveness[5]. This requires developing both process-related metrics, which track planning and resource allocation, and outcome-related metrics, which assess performance during shocks and stresses[5]. As a model, the U.S. federal government developed a common set of five process-related indicators for its Climate Adaptation Plans, covering whether resilience is integrated into budgeting, data systems are updated, policies incorporate nature-based solutions, supply chains are evaluated for risk, and staff are trained[5]. To be effective, indicators must be aligned with stakeholder priorities[14]. A project in New York City analyzed 41 community-based resilience plans to identify shared goals and develop corresponding indicators[14]. The ultimate goal is to create user-friendly tools, such as a 'resilience report card,' that can help officials triage funding, enable advocates to build public pressure for government action, and empower communities to guide local resilience planning[14].

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalized discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).