Foundations of Workplace Automation

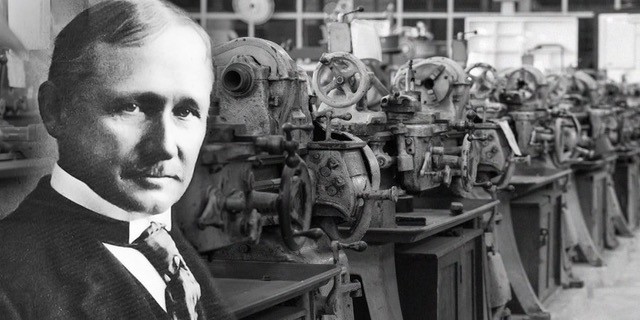

The roots of modern work organization can be traced back to the early 20th century with the advent of Taylorism. Frederick Winslow Taylor introduced Scientific Management in 1911 by breaking work processes into small, standardized tasks to increase productivity and reduce operational costs[2]. This systematic division of labor ensured that workers performed tasks in a predetermined sequence, with management responsible for planning and supervision[2].

Early Mechanization and the Industrial Revolution

The transformation from manual to mechanized work started during the Industrial Revolution. Factories rapidly adopted mechanized equipment, and workers saw their livelihoods threatened by machines that could produce goods more efficiently[1]. This period witnessed significant unrest, including the actions of the Luddites, who famously destroyed looms in protest of machines that undermined traditional labor practices[1]. Archival imagery of early factory floors, steam-powered machines, and scenes of worker protests would help illuminate this turbulent era.

Assembly Line and Mass Production

Shortly after these early mechanization efforts, the concept of the assembly line revolutionized manufacturing. By breaking down complex processes into manageable and repetitive tasks, assembly lines made mass production both feasible and more efficient[7]. The automotive industry, in particular, benefited from robotics and automation that increased productivity while also leading to workforce dislocation in some cases[1]. Archival photographs of bustling assembly lines and early robotic systems vividly capture the spirit of this transformation.

The Evolution of Automation and Computerization

The latter half of the 20th century saw the integration of computing and information and communication technology (ICT) into traditional manufacturing and office environments. With the advent of computers, routine tasks in clerical and manufacturing work were automated, leading to what has been described as labor market polarization[3]. These technological changes shifted the demand toward high-skill workers and away from routine middle-skill jobs, creating significant economic shifts that continue to influence labor markets today[3].

From Robots to Intelligent Machines: Rise of AI

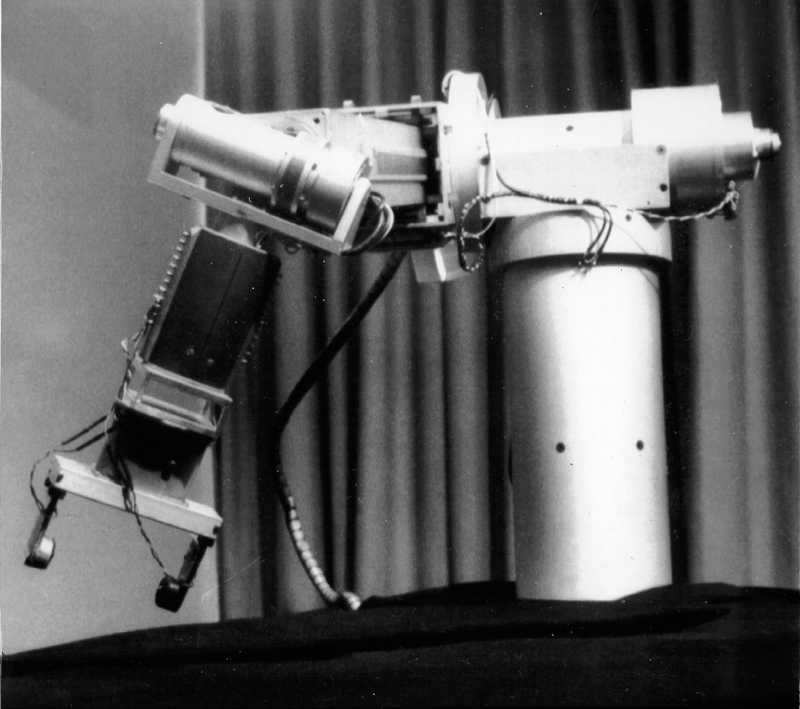

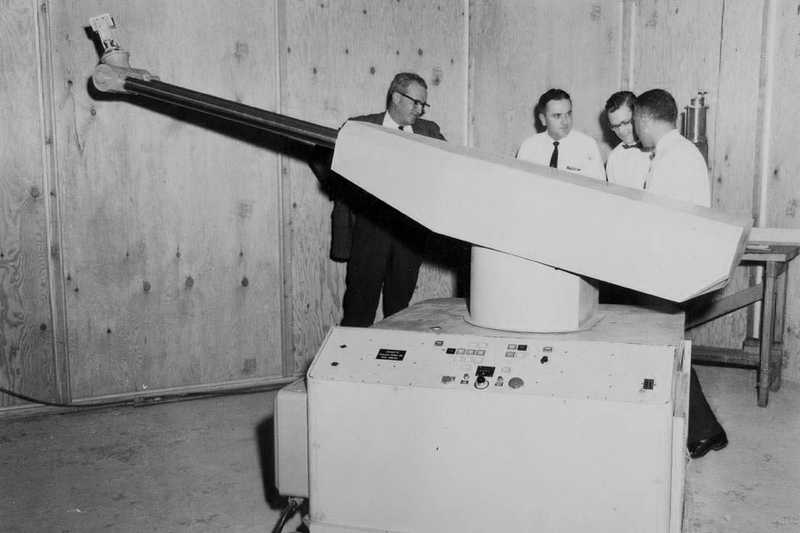

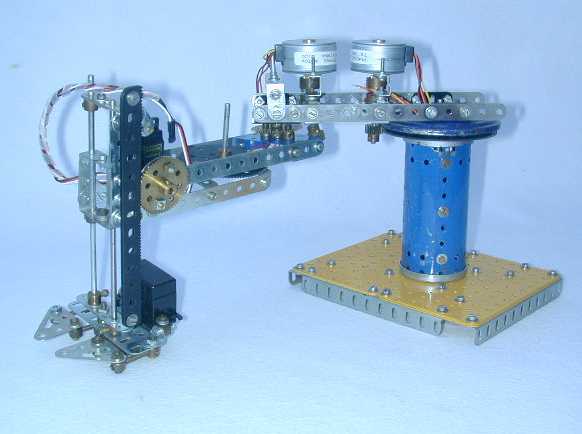

The emergence of robotics and artificial intelligence marks the latest phase in the evolution of workplace automation. In 1954, the introduction of the Unimate – the first industrial robot – revolutionized manufacturing by performing repetitive tasks in automotive production[6]. Over the decades, AI has grown from a novelty application, such as a checkers-playing program, into a powerful driver of innovation that automates cognitive, physical, and even some social tasks[6]. Today, advanced machine learning algorithms and neural networks perform tasks ranging from predictive analysis in finance to image recognition in healthcare, while also offering the potential to complement rather than simply replace human labor[1]. Archival images that juxtapose early industrial robots with modern AI laboratory setups would provide a visual narrative of technological progress.

Labor Movements and Economic Shifts

Parallel to these technological advances, the labor movement evolved in response to shifting work conditions. Labour unions emerged during the Industrial Revolution to advocate for improved working conditions, fair wages, and reasonable hours—a struggle that continues as new technologies reshape the nature of work[5]. In more recent times, as automation and AI threaten traditional jobs, discussions around universal basic income, reskilling programs, and even digital forms of labor organization have intensified[1]. Furthermore, the concept of Meta-Taylorism has surfaced, where digital labor marketplaces automate management functions and deploy human workers primarily for data labeling and training AI systems[9].

Archival Imagery Suggestions

A comprehensive visual narrative for this history would include archival imagery such as early factory settings during the Industrial Revolution, protests by the Luddites, and photographs of Taylor analyzing time studies on the shop floor. Images showing assembly lines in full operation during the early days of mass production alongside early robotic arms in automotive factories can also enrich the narrative. More modern images may include scenes of computer-assisted manufacturing, workers in digitally transformed offices, AI laboratories, and concept art of digital labor marketplaces. These visuals not only document the evolution of technology but also highlight the human aspect of these economic transformations.

Conclusion and Future Implications

The journey from Taylor's Scientific Management to the sophisticated AI systems of today demonstrates a continuous evolution of work design driven by technological advancements. Each pivotal leap—from mechanization during the Industrial Revolution to assembly-line automation, and now the rise of intelligent machines—has reshaped labor markets, influenced economic policies, and challenged traditional notions of work[4]. As we look to the future, balancing automation with job creation and ensuring equitable labor practices remains a critical challenge for governments, businesses, and workers alike[3]. This historical narrative serves not only as a reminder of past transformations but also as a guide for navigating the complexities of emerging technologies in the workplace.

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalized discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).