Introduction to Sneaker Botting and the Collectible Market

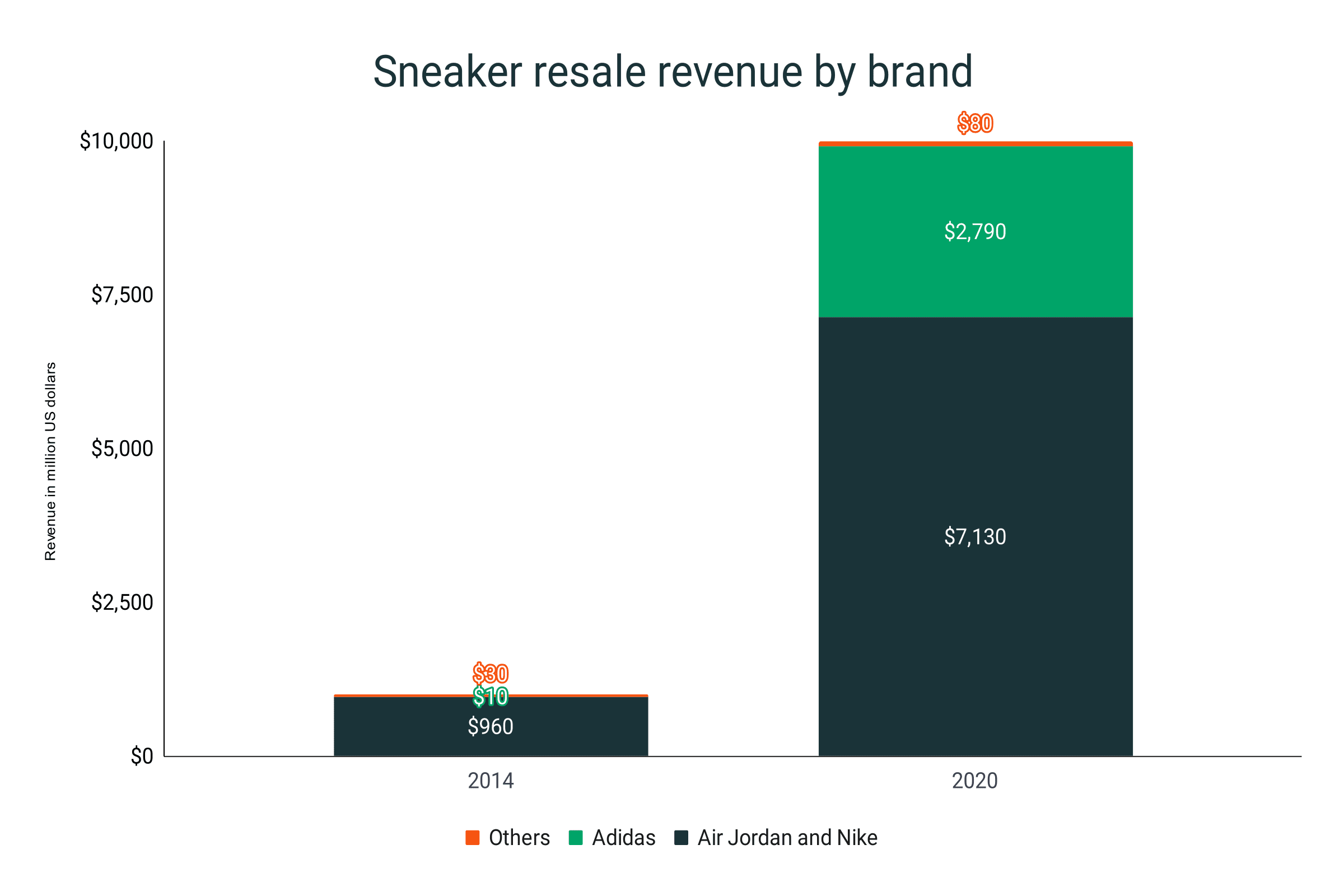

The sneaker resale market has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry, where collectible sneakers drive intense enthusiasm among buyers, resellers, and investors. Over the last decade, automated software—commonly known as sneaker bots—has become a tool for acquiring limited-edition releases rapidly, providing users with the potential to flip these highly coveted products for a substantial profit. As one expert from earlier analyses noted, sneaker botting requires constant adjustments and significant capital, making it a high-stakes game[1][4]. The practice leverages the principles of supply and demand in a market where scarcity drives prices, yet the increasing saturation has raised the entry bar considerably.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Sneaker Bots

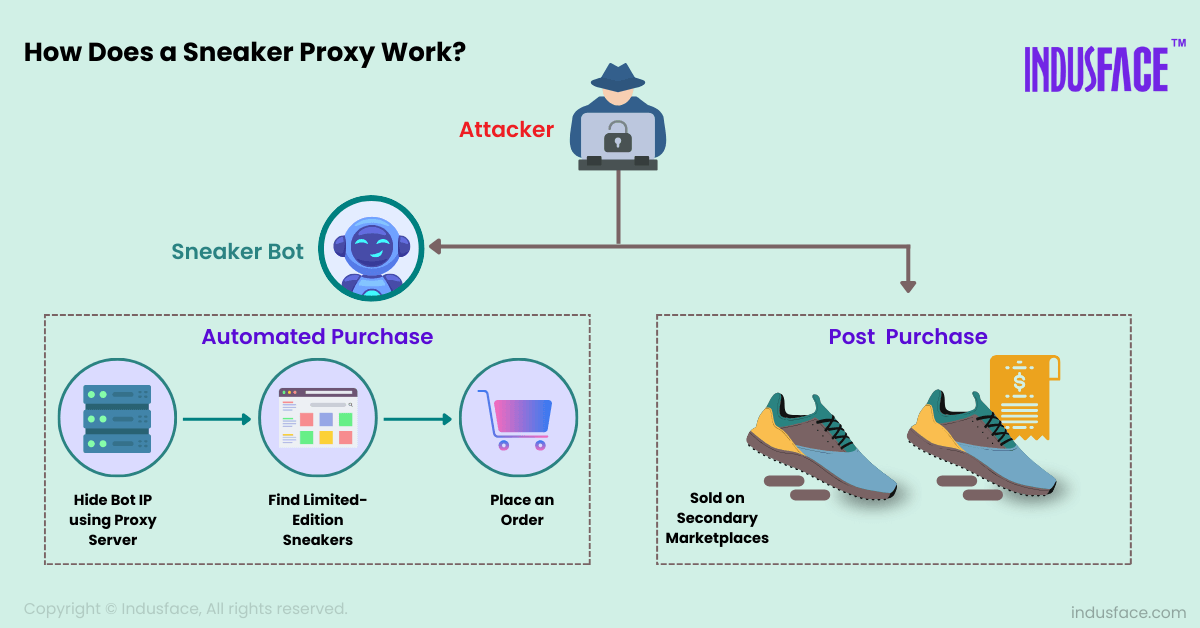

Modern sneaker bots have evolved far beyond simple automated loops. They now increasingly integrate artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques to predict sneaker demand and adapt in real time to sophisticated anti-bot systems. As detailed by technology insights, future bot systems will analyze browsing patterns and purchase speeds to mimic human behavior nearly flawlessly, enhancing their ability to predict which drops may yield the highest resale margins[5]. This dynamic adaptation allows them to automatically adjust for changes on retailer platforms, from recalibrating CAPTCHA solving techniques to integrating with built-in proxy pools. By leveraging AI, these bots are designed to forecast demand trends and optimize checkout processes, thereby increasing the chance of successfully securing high-demand sneakers at retail prices[2][3].

Automated Purchasing and Resale Profitability

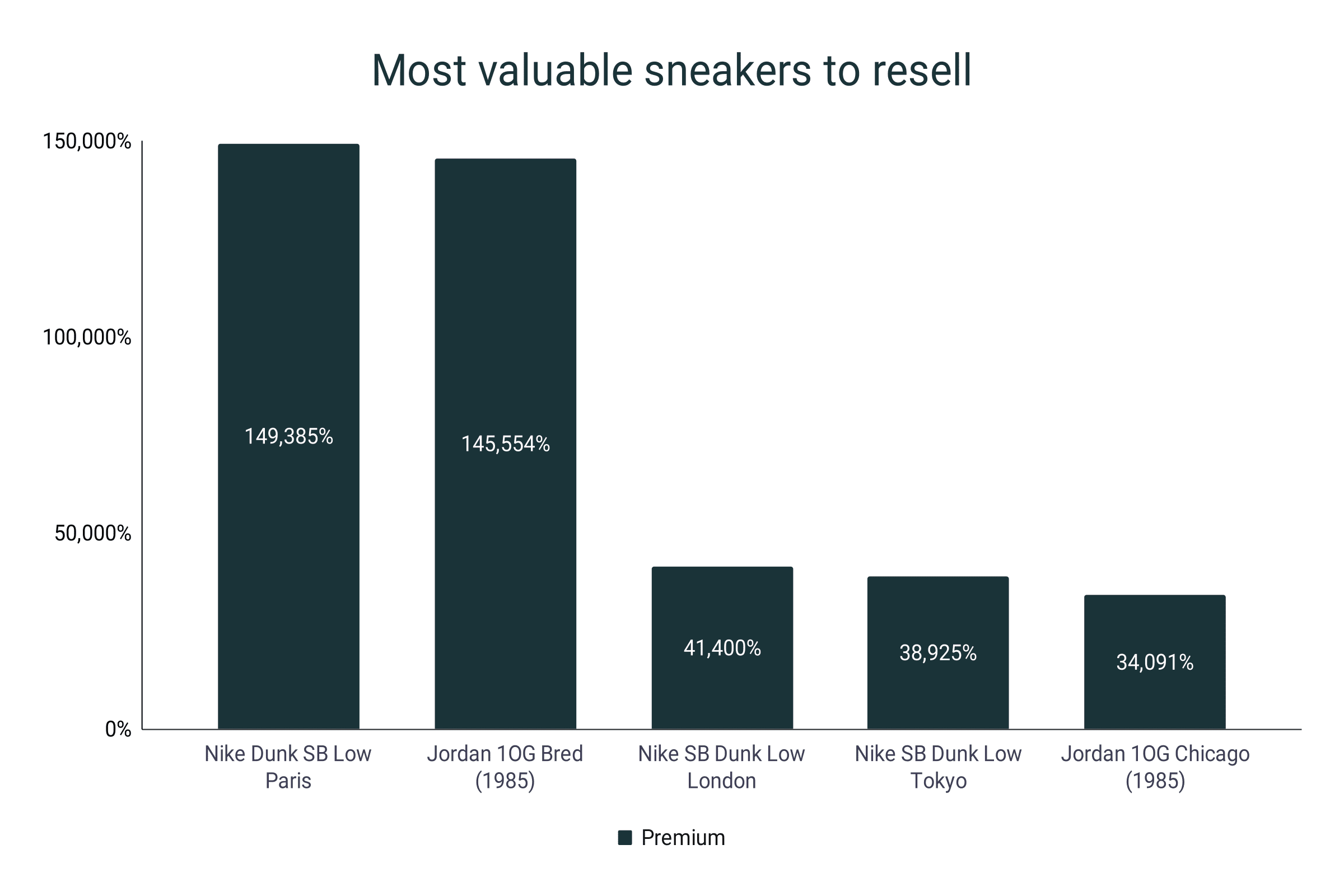

Sneaker bots enable a level of buying power that manual buyers simply cannot match. By automating the process of filling out payment and shipping information and bypassing queue systems, these intelligent programs can complete transactions in milliseconds. According to research, this speed advantage has become crucial, given that many high-end sneaker drops are purchased by bots within seconds of release[3][11]. The profitability of flipping sneakers varies widely. While resellers once enjoyed 50% or more margins on certain models, market saturation and improved anti-bot measures have compressed profit margins over time[1][8]. Nonetheless, successful users have reported sizable profits—sometimes into the five-figure monthly range—in spite of rising startup costs, which can easily exceed $5,000 when purchasing a robust setup or subscribing to premium bot services[1][4].

Capital Requirements, Risks, and Market Saturation

While the promise of fast profits is alluring, the sneaker botting game is not without its risks. The investment in a competitive AIO (all-in-one) bot setup may require upfront costs in the range of $3-5K, along with a significant operational bankroll to purchase inventory for resale[1]. Furthermore, the high competition has led to increased expenses in acquiring advanced proxy networks and in staying ahead with constant updates to both bots and countermeasures deployed by retailers[5]. For instance, retailers like Nike, Adidas, and others have significantly improved anti-bot defenses, including CAPTCHA challenges, IP reputation analysis, and machine learning-based behavior detection[2]. Moreover, hidden fees such as transaction charges, storage costs, and shipping expenses can quickly erode profit margins[8]. Market saturation poses another challenge; as resellers and automated buyers dominate high-demand releases, the resale market can become oversupplied, driving down prices and reducing overall margins[9].

Legal and Ethical Considerations

The use of sneaker bots exists in a regulatory gray area. Although sneaker botting itself is legal in the United States, it often violates retailer policies, and the practice has raised ethical concerns about fairness and consumer access[10]. Legal frameworks such as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and related legislation have been referenced in discussions about automated purchasing, as they underline the possible repercussions of unauthorized access to retailer systems[10]. Ethically, sneaker bots contribute to an uneven playing field where only those with sufficient capital and technical expertise can succeed, leaving average consumers frustrated and locked out of limited releases[10]. Additionally, the potential for fraud, misleading marketing practices, and market manipulation are ever-present risks in this evolving ecosystem.

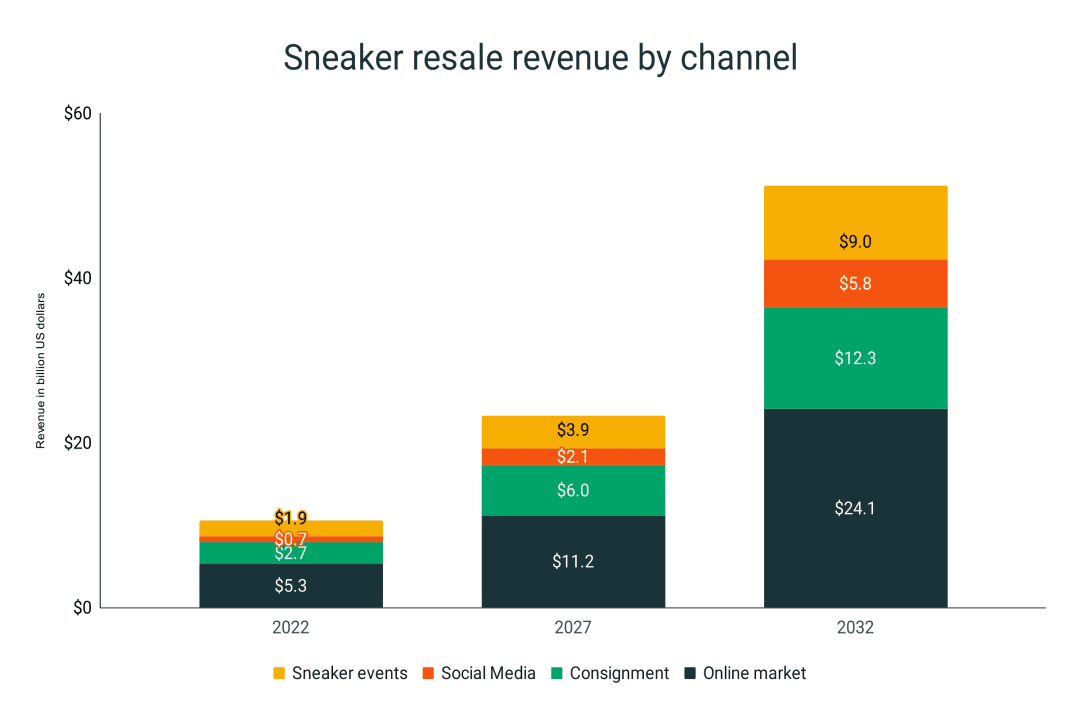

The Future Outlook for Sneaker Botting

Looking ahead, the sneaker resale market is expected to continue evolving amid technological advancements and shifting consumer behaviors. The integration of cloud-based systems, improved proxy solutions, and decentralized networks may further refine how bots operate and evade detection[5]. At the same time, as market saturation leads to diminished profit margins on some models, resellers are likely to diversify their portfolios—often branching out into alternative collectible markets—to stabilize revenue streams[1]. Despite these challenges, the allure of automated purchasing strategies remains strong. For those willing to invest in a mix of cutting-edge technology, capital, and market insight, sneaker botting can still represent a viable strategy to flip collectible sneakers profitably, although not without substantial risk and ongoing adaptation[1][6][7].

Conclusion

In summary, the use of AI-driven sneaker bots to predict demand, automate purchases, and flip collectible sneakers for profit is an evolving and competitive field. While the integration of sophisticated technologies such as machine learning significantly enhances the effectiveness of bots, the associated risks—ranging from high capital investment and operational costs to legal and ethical challenges—must be carefully managed. As market saturation increases and retailer countermeasures become more robust, success in this arena will depend on continuous innovation, sound strategy, and informed risk management. For enterprising individuals with the resources and technical know-how, sneaker botting remains a high-reward albeit high-risk venture in the ever-changing world of collectible sneakers[1][2][5][3][9].

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalized discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).