Early Scottish Maritime History and the Need for Light-Houses

The Scots, recognized for their strong maritime spirit among European nations, were geographically positioned to become adept seafarers[1]. Their trade routes to Hanseatic Towns and other European commercial centers were longer than those of their English counterparts, requiring them to navigate treacherous waters and exposing them to dangers such as enemy ships and inclement weather[1]. Scotland's frequent conflicts with northern powers further necessitated a strong navy to safeguard its commerce[1]. Alliances with foreign entities and the annexation of the Orkney and Shetland Islands also expanded Scotland's foreign trade and solidified its coastal dominion[1].

However, it was the unification of the crowns and kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland that unleashed the full maritime potential of these nations[1]. By the mid-18th century, there was a growing understanding of the strategic importance of the Scottish Highlands, which led the government to promote fisheries, establish towns and harbors, and improve transportation networks through roads and canals[1]. The increasing coastal commerce in Scotland, spurred by British fisheries and the manufacture of kelp for marine alkali, highlighted the need for improved navigational aids[1]. The dangers and length of voyages around Scotland's coasts, particularly near the Orkney and Western Islands, underscored the necessity of light-houses and accurate charts[1].

Early Efforts to Chart the Scottish Coast

Early efforts to improve navigation relied largely on rudimentary guides[1]. The journals and charts from the 1540 voyage of James V, who with twelve ships sailed around a large portion of Scotland, served as a crucial, and perhaps primary, navigational tool for centuries[1]. Later, around 1740, Rev. Alex Bryce created a geometrical survey of the northwest coast of Scotland at the request of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh[1]. Further advancment was made in 1750 with Murdoch Mackenzie's charts of the Orkney Islands, which were later extended to the Western Highlands and Islands under government commission[1]. Despite these improvements, large shipping vessels continued to avoid the narrower passages, preferring the more hazardous but better-known routes along the open sea[1]. The construction of light-houses was therefore viewed as critical to guiding ships safely along these routes[1].

The Establishment of the Northern Light-House Board

The demands of shipmasters and owners were heard, and in 1786, Mr. DEMPSTER of Dunnichen brought the idea of a Light-house Board to the Convention of Royal Boroughs of Scotland[1]. This resulted in the passage of an act establishing the board and authorizing the construction of four light-houses in northern Scotland: at Kinnaird Head, on the Orkney Islands, on the Harris Isles, and at the Mull of Kintyre[1]. The act also introduced a levy on ships to fund these projects[1].

The initial commissioners included prominent officials such as His Majesty's Advocate and Solicitor-General for Scotland, the Lord Provosts and First Bailies of Edinburgh and Glasgow, the Provosts of Aberdeen, Inverness, and Campbeltown, and the Sheriffs of various northern counties[1]. Thomas Smith was nominated Engineer to the Board[1].

Sir James Hunter-Blair, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, convened the first meeting of the board where he stressed the importance of the new act and how imperative it was to gather as much advice from experienced engineers as possible[1].

Early Light-House Construction and Financial Challenges

Initial efforts focused on corresponding with landowners to acquire sites for the light-houses[1]. By December 1787, a light-house was erected on Kinnaird Castle[1]. The construction of the Mull of Kintyre Light-house proved more challenging due to its remote location, and the light was not exhibited until October of the following year[1]. The early progress of the Northern Light-houses was impeded by limited funds, stemming from a light-house duty deemed too small[1]. To address this, Parliament passed an act in 1788, increasing the duty and enabling the Commissioners to borrow additional funds for their operations[1]. By 1789, light-houses were also erected and lit at Island Glass in Harris and on North Ronaldsay in Orkney[1].

Later Light-House Constructions and Financial Management

ThePladda light-house was completed in 1790, equipped with a distinguishing feature in 1791, showing two distinct lights[1]. The increasing demands for additional light-houses and better management of the existing ones led to the appointment of annual inspections and supply vessels[1]. In 1794, work began on the Pentland Skerry Light-houses, with the author commencing his service for the Board[1].

An act passed in 1798 incorporated the Commissioners into a body politic, allowing them to hold stock and invest surplus funds[1]. By 1806, the Inchkeith Light-house became operational, marking a new era in the Board's construction, with the buildings becoming more permanent and substantial[1]. Notably, the account highlights the benefits of the Board's management, stating, "...that the progress of the Light-house works proceeded, without experiencing any interruption from want of funds"[1].

The Bell Rock Light-House

Several petitions were made to the commission to provide some sort of aid near the Bell Rock due to the immense danger and volume of ship traffic in the area[1]. Due to limited funds as of 1803, the erection of a light-house on the Bell Rock was not feasible, and the further consideration was delayed[1].

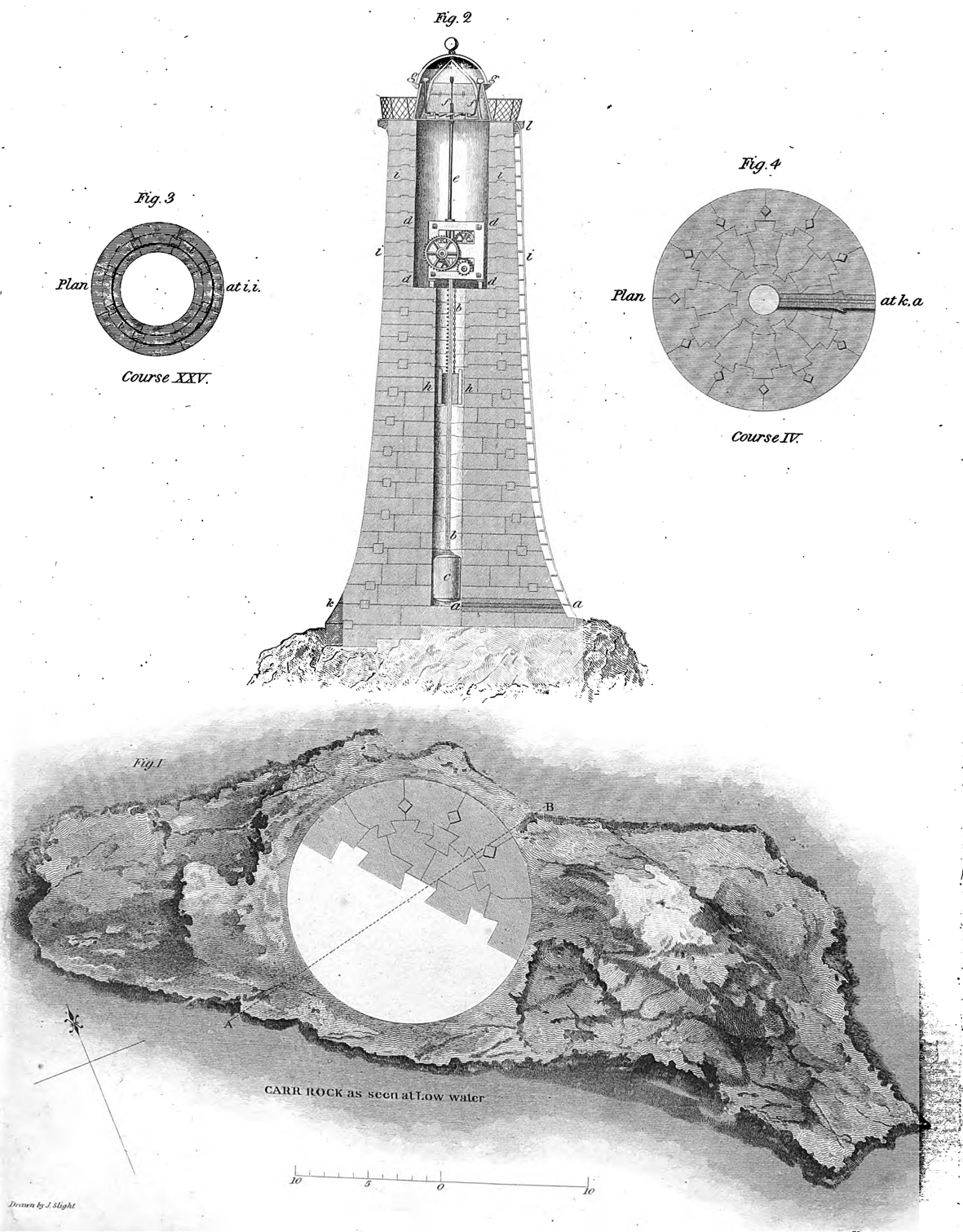

The construction of the Bell Rock Light-house between 1807 and 1810 marked a significant endeavor[1]. Despite problems with supply delay the effort, the light was exhibited February 1, 1811[1]. The name, situation, and dimensions of the rock, the designs for the light-house, the act passed by the Lord Advocate Erskine, and the report of the House of Commons committee were important steps in the process[1]. Special problems called for both a floating light and masonry construction on the rock itself[1].

Get more accurate answers with Super Pandi, upload files, personalized discovery feed, save searches and contribute to the PandiPedia.

Let's look at alternatives:

- Modify the query.

- Start a new thread.

- Remove sources (if manually added).